Croatia is a country located in Central Europe, bordered by Slovenia, Hungary and the Adriatic Sea. According to homosociety, it has a population of around 4.1 million people and an area of 56,594 square kilometers. The capital city is Zagreb while other major cities include Split and Dubrovnik. The official language of Croatia is Croatian but many other languages such as Hungarian and Italian are also widely spoken. The currency used in Croatia is the Croatian Kuna (HRK) which is pegged to the Euro at a rate of 1 HRK : 0.13 EUR. Croatia has a rich culture with influences from both Central European and Mediterranean cultures, from traditional music such as klapa to unique art forms like lace-making. It also boasts stunning natural landscapes such as Plitvice Lakes National Park and Kornati Islands National Park which are home to an abundance of wildlife species.

Croatia’s history begins with Illyria, a landscape on the Balkan Peninsula that included today’s Croatia. This area was colonized by the Greeks from the 7th century before our time, and later by the Romans. Around 600 according to our time, Slavic tribes immigrated. The area was Christianized in the 8th century.

Croatia was an independent kingdom from 910 to 1091. Thereafter it was subject first to Hungarian, later Austro-Hungarian rule between 1102 and 1918. From 1918 to 1992, Croatia was part of Yugoslavia. See abbreviationfinder for geography, history, society, politics, and economy of Croatia.

Prehistory

The oldest known population in the area that is today Croatia was the Illyrians from 1200 BCE, who later mingled with the Celts. The Greeks created colonies along the Dalmatia coast from the 7th century BCE. and the Romans from the 4th century BCE.

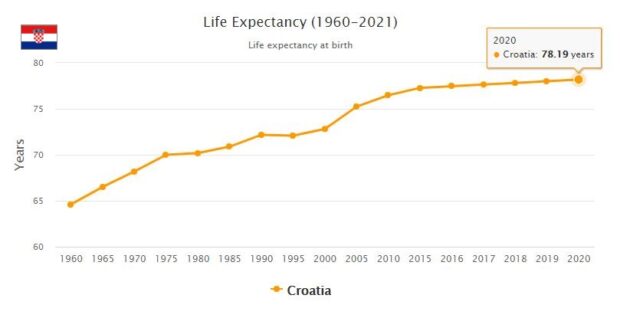

- COUNTRYAAH.COM: Provides latest population data about Croatia. Lists by Year from 1950 to 2020. Also includes major cities by population.

The Adriatic coast made up the Roman Illyrian province, later the province of Dalmatia, while the province of Pannonia encompassed the interior of the country at Sava and the Danube. Testimony of Roman culture is the Amphitheater in Pula, Diocletian’s Palace in Split and Forum in Zadar.

Early Middle Ages

Around 600 possibly immigrated Slavic and Avaric tribes. It is believed that the Croats may have been an Iranian tribe (the name is not Slavic) who subjugated the slaves and mixed with them. Eventually, the former Romanesque population along the Adriatic gradually rose in the Slavic – like the Romanesque city of Ragusa, which became the Slavic Dubrovnik.

The Croatians were Christianized from the west in the 8th century. In 845, the Croatian prince Trpimir founded a Croatian state and a dynasty that ruled for 250 years. First Branimir (879–892), titled Dux Croatorum, created a diocesan seat in the town of Nin by Zadar. First Tomislav (910–928) extended the kingdom to Slavonia, Istra and Dalmatia, and in 924 took the title king.

The empire was weakened through battles with Venice, but experienced a new high during King Petar Krešimir 4 (1058–1074). In 1091, the Trpimirović dynasty died out, and in 1102 Croatia was defeated by the Hungarian king Koloman.

Hungarian rule (1102–1918)

The union of workers with Hungary, Pacta Conventa, in effect meant that Croatia was subject to Hungarian supremacy for the next 800 years (until 1918). However, Croatia retained its political identity. “The Kingdom of Croatia, Slavonia, Dalmatia” (Regnum tripartium) had a governor, Ban, who heads. The power lay with the great feudal lords, who led the parliament, Sabor, and who were also represented in the Hungarian parliament.

From the 13th century, Dalmatia came under Venetian rule. During the Renaissance a flourishing Croatian culture arose in Dalmatia (cities such as Zadar, Šibenik, Split, Hvar) and the Dubrovnik urban republic, influenced by the Italian Renaissance. Shipping and trade made Dubrovnik a rich city where culture flourished in the 1400s-1600s.

Subject to house Habsburg

From the mid-1400s, when Bosnia came under Turkish rule, Croatia resisted Turkish attacks on the Hungarian defeat of Mohács in 1526. For 150 years, parts of Croatia-Slavonia were under Turkish rule, along with Hungary. The rest of Croatia, the Zagreb area, became subject to the Habsburg house in 1526, when the nobility chose the Habsburg Ferdinand 1 as king.

In 1578, the “Military Frontier” was established as an Austrian buffer zone against the Turks, and many Serbian refugees settled here as border soldiers (later Krajina). The Turks were expelled from the Croatian territories by the Karlowitz peace in 1699, and for over 200 years the whole of Croatia-Slavonia was part of the Habsburg Empire. Dalmatia was under Venice until 1797, then part of Napoleon’s Illyrian provinces, and from 1815 under Austria.

Croatian nationalism

At the beginning of the 19th century, opposition to Hungary’s pressure and Croatia’s inferior position within the Habsburg monarchy grew. The national movement, also known as the “Illyrian Movement” (1830-1848), created a common Croatian written language. The movement was both Croatian nationalist and oriented towards South Slavic (Pan- Slavic). The revolution of 1848 meant the end of this business. Croatia’s governor (ban) Josip Jelačić helped the emperor defeat the revolutionary Hungarians, but Croatia gained no autonomy.

Croatia became an Austrian krone country, and the period 1849-1860 was characterized by a reactionary Austrian policy. After 1860, Parliament, Sabor, began to function again. A spokesman for the National Party that wanted Croatian autonomy in union with Hungary, was Bishop Strossmayer, who championed the Yugoslav (South Slavic) idea and created a science academy in Zagreb in 1866 under the name of the Yugoslav Science Academy.

A more Croatian nationalist direction was represented by the leaders of the Justice Party, Ante Starčević and Eugen Kvaternik, who wanted territorial unification and autonomy for Croatia and opposed Serbian expansion plans.

After the double monarchy of Austria-Hungary was established in 1867, Hungary and Croatia signed a similar agreement (nagodba) in 1868. In reality, Croatia’s autonomy was very limited, and the influence of the Croats in budget and tax matters was minimal. However, under Croatian governor Ivan Mažuranić (1873-1880), Croatian culture was strengthened. Following Austria-Hungary’s occupation of Bosnia-Herzegovina in 1878, the Croats wanted a collection of the South Slavic areas within the empire, as a counterbalance to Hungarian influence. The emperor refused, and the anti-Austrian atmosphere grew.

Croatian-Serbian cooperation

Towards the end of the 19th century, under the rule of the Hungarian governor of Croatia, Khuen-Hedervary (1883-1903), the Hungarian pressure became stronger. After anti-Hungarian riots in 1903, and regime change in Serbia the same year, the idea of a collaboration with the Serbs gained greater support.

In 1906, the Croat-Serbian coalition won the elections and remained in power until 1918. Cooperation with Serbia was seen as a counterbalance to Hungary and Austria. Croatian exile politicians, including Ante Trumbić and Frano Supilo, were active during the First World War in the Yugoslav Committee, which advocated a common South Slavic state after the war. Towards the end of the war, Croatian fears of Italian expansion made this idea more relevant.

Croatia in Yugoslavia (1918–1992)

On October 29, 1918, the Croatian Parliament broke with Austria-Hungary, declared Croatia independent, and transferred its authority to the National Council, an association of South Slavs in the Habsburg Parliament. In November, the National Council decided to join forces with Serbia in a new state. The Kingdom of Yugoslavia (“South Slavia”) was proclaimed on December 1, 1918.

Stjepan Radić

The merger was met by the most important Croatian politician of the interwar period, Stjepan Radić, who in 1904 had formed the Croatian peasant party with his brother Antun. Soon, many Croats were disappointed with the new state, which was heavily centralized and dominated by the Serbs. Sabor, the Croatian parliament, was repealed. Parts of the Croatian territory were subject to Italy; including the cities of Rijeka and Zadar, the Istra Peninsula and several islands in the Adriatic.

Stjepan Radić came into strong opposition to the Belgrade regime, and on June 20, 1928, he and two other Croatian MPs were shot down in the Belgrade Parliament. Radić died a month later. The attack on Radić, the most popular politician in Croatia, led the Yugoslav king Aleksander to impose dictatorship in 1929.

Ustasja and the fascist regime

The Croatian exile organization Ustasja was involved in the assassination of King Alexander in Marseille in 1934. Under the reign of Prince Paul, the regime was made easier, and in 1939 the head of the Croatian Peasant Party, Vladko Maček, and Prime Minister Cvetković entered into a compromise on Croatia’s extended autonomy within Yugoslavia. The so-called Banatet Croatia covered Croatia and parts of Bosnia and Herzegovina. However, the outbreak of the Second World War meant that this solution did not last long.

Following Germany and Italy’s conquest of Yugoslavia in April 1941, the independent state of Croatia was proclaimed, with Ustasja leader Ante Pavelić leading. The Ustasja regime carried out a brutal ethnic cleansing of the Serbian population, especially in Bosnia; over 300,000 Serbs lost their lives in the Croatian fascist state. Notorious was the Jasenovac concentration camp. But also resistance to fascism was considerable in Croatia, and in 1943 Croatia’s anti-fascist liberation council was formed.

Croatia under Tito

In 1945, Croatia became one of the six sub-republics of Josip Tito’s communist federal state. Many Croatian soldiers and civilians, as well as prisoners in Slovenia and Austria, were killed by Tito’s partisans just after the liberation. The archbishop of Zagreb, Alojzije Stepinac, was sentenced in 1946 to 16 years in prison, accused of cooperating with the Ustasja regime. Of the Croats, this was seen as an anti-Croatian move by Tito, who was himself a Croat, but who deposed and liquidated the Croatian communist leader Andrija Hebrang in 1948-1949.

In the post-war period, Croatia, which from ancient times belonged to the richer part of Yugoslavia, experienced an economic expansion. Tourism on the Adriatic Sea provided Yugoslavia with 50 percent of foreign exchange revenues. But many Croats believed that too much of the surplus disappeared from the Republic, even after Yugoslavia became strongly decentralized in the 1960s and 1970s. Many Croats had to go abroad, especially Germany, as foreign workers.

In the 1970s, a Croatian national movement emerged among intellectuals, who in 1970-71 received wide popular support and support from the Liberal Party leadership in Croatia. After student demonstrations in Zagreb, “the Croatian spring” was defeated by Tito in December 1971, and there was extensive cleansing.

From 1972 to 1990, a dogmatic Communist Party ruled in Croatia.