Egypt is a country located in North Africa, bordered by Libya and the Mediterranean Sea. According to homosociety, it has a population of around 100 million people and an area of 1,010,000 square kilometers. The capital city is Cairo while other major cities include Alexandria and Giza. The official language of Egypt is Arabic but many other languages such as English and French are also widely spoken. The currency used in Egypt is the Egyptian Pound (EGP) which is pegged to the US Dollar at a rate of 1 EGP : 0.062 USD. Egypt has a rich culture with influences from both African and Middle Eastern cultures, from traditional music such as taarab to unique art forms like papyrus making. It also boasts stunning natural landscapes such as Siwa Oasis and White Desert National Park which are home to an abundance of wildlife species.

Prehistory

The prehistory of Egypt is linked not only to the Nile but also to the whole of northeastern Africa. Changes in the course of the Nile and of temperature and precipitation, especially at the end of the Pleistocene, resulted in drying of varying degrees, from the highlands of eastern Africa to upper Egypt, with consequences in the form of significant differences in the Nile floods in central and lower Egypt.

The earliest finds from the production of stone implements in Egypt come partly from finds collections in disturbed stock sequences on the Nile River terraces, partly from undated quarries and manufacturing sites found in situ near Wadi Halfa and probably from the acheulé. See abbreviationfinder for geography, history, society, politics, and economy of Egypt. Utility complexes from the later levalloisia-mustache tradition have been found upstream of Luxor. Downstream, tools from the Middle Paleolithic must have been found along with bones of wild beasts; The findings show kinship with the Athenian culture in Southern Sahara. Finds of later implements, e.g. at Khour Mousa, dated to about 37,000 BC, encompasses chip-based complexes similar to those of the Daban culture. These are followed by a number of distinct gear complexes from the period 15,000–10,000 years ago and indicate more diversified nutritional traps than before, among other things.

In the Nile Valley, pollen analyzes from Esna indicate that some crops such as wild grains may have taken place some 12,000 years ago. Livestock was probably domesticated in North Africa (Sahara) about 9,000 years ago, from where livestock management later spread to the Nile Valley. Remains of round huts with stone foundation indicate that a more settled life began 9,000 years ago in the Dakleh oasis. About 8,000 years ago barley was grown and livestock management in Nabta Playa, today desert. The settlement consisted of house rows and storage pits. contained wild sorghum and millet. An increasing number of bones of sheep are found in 7,000 year old bargains. At the same time, pottery appears in Nubia and has been found in both Upper and Middle Egypt, eg. in the Badare region. About 6,000 years ago, Fayyum and the delta area were populated by small peasant groups living in oval huts in settlements of up to 18 ha, e.g. Merimda Beni Salama. Barley, bucket and flax were grown and the domesticated animals included cattle, goats, pigs and donkeys.

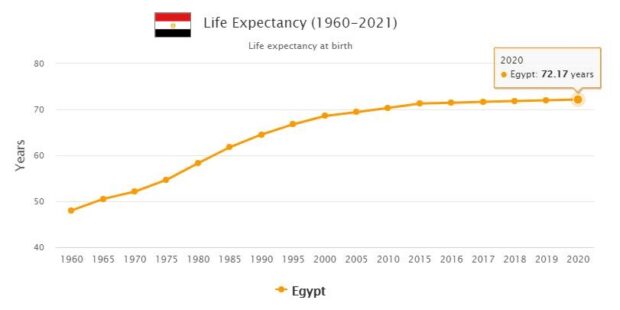

- COUNTRYAAH.COM: Provides latest population data about Egypt. Lists by Year from 1950 to 2020. Also includes major cities by population.

About 6,000 years ago, upper and middle Egypt began to develop a cultural phase, Nagada I, which was characterized by expanded village development, population growth and changed social organization. is reflected in funeral customs. About 5,600 years ago, smaller cities emerged, e.g. Hierakonpolis, Naqada and This. At the same time, changes in religion took place. Regional states were established and followed 5,000 years ago (ie, about 3000 BC) by the first united state in Egypt.

History

Ancient Egypt lacks its own real history writing; the first coherent account was made by Herodotus in the 14th century BC The division of the Pharaohs’ time into dynasties (see table) was made about 280 BC. by the priest Manetho, based on preserved lengths of the cave; Consequently, a very varied source material must be used in the preparation of the country’s history.

Dynasties and important Pharaohs

| Archaic period (ca. 3000-2700 BC) | |

| Dynasty 1–2 | Narmer, “Scorpio”, Aha, Khasekhemwy |

| The Old Kingdom (ca. 2700–2270 BC) | |

| Dynasty 3 | Djoser, Huni |

| Dynasty 4 | Sneferu, Cheops, Chefren, Mykerinos |

| Dynasty 5 | Userkaf, Sahure, Neuserre, Unas |

| Dynasty 6 | Teti, Pepi, Pepi II |

| First intermediate period (ca. 2270-2040 BC) | |

| Dynasty 7-10 | |

| The Middle Kingdom (c. 2040–1675 BC) | |

| Dynasty 11 | Mentuhotep I – III |

| Dynasty 12 | Amenity I, Sesostris I, Amenemeth II, Sesostris II, Sesostris III, Amenemeth III, Amenemeth IV |

| Dynasty 13 | |

| Second Intermediate Period (ca. 1675–1575 BC) | |

| Dynasty 14–17 | Partial Hyksos reign: Khian, Apopis |

| The New Kingdom (c. 1575–1087 BC) | |

| Dynasty 18 | Ahmose, Amenhotep I, Thutmosis I, Thutmosis II, Hatschepsut, Thutmosis III, Amenhotep II, Thutmosis IV, Amenhotep III, Akhenaton (= Amenhotep IV), Smenkhare, Tutankhamun, Eje, Horemheb |

| Dynasty 19 | Ramses I, Sethos I, Ramses II, Merenptah |

| Dynasty 20 | Sethnakht, Ramses III, Ramses IV-XI |

| Third Intermediate Period (1087–663 BC) | |

| Dynasty 21 | Smendes, priest kings of Thebe: Herihor |

| Dynasty 22-24 | Libyan Pharaohs: Sheshonk I, Osorkon II |

| Dynasty 25 | Nubian Pharaohs: Pianchi, Shabaka, Taharka |

| The Late Times (663–343 BC) | |

| Dynasty 26 | Psammetichos I, Necho, Psammetichos II, Apries, Amasis, Psammetichos III |

| Dynasty 27 | Persian great kings as pharaohs: Cambyses, Dareios I, Xerxes, Artaxerxes, Dareios II |

| Dynasty 28–29 | |

| Dynasty 30 | Nektanebos I – II |

| Ptolemy (305-30 BC) | |

| Ptolemy I – XV, Cleopatra VII | |

| Roman times (30 BC – 395 AD) | |

| Byzantine (East Roman) Time (395–640) | |

Archaic Age (Dynasty 1–2, ca. 3000–2700 BC)

The geographical space of Pharaonic Egypt was the Nile Valley north of the first cataract of Assuan and Delta. The archaic kingdom meant a consolidation of the cultural uniqueness developed during the Naqada cultures. With the dominion over Lower and Upper Egypt followed the central, administrative recovery of the country’s natural resources, the regulation of the Nile’s annual floods, the opening of quarries and mines (copper and gold) and the organization of the country’s labor force. Scripture was introduced to serve the administration, and in architecture and art new forms of language were created to express the needs of power and religion.

Menes, the first pharaoh (the same as king), was for later Egyptians a legendary cultural hero, though his historical existence is questionable. The items that may best express the history of early Egypt are the ceremonial makeup palettes and club heads, which tell in relief about the national unification. Kings like Narmer, “Scorpio” and Aha in the 1st Dynasty emerge as foreground figures. They ruled under the patronage of Horus the god, by which the king was divine; world ruler, however, was the sun god Re.

The two regions included two residences, Abydos and Memphis (Saqqara). The early kingdom had trade contacts with Sinai (copper mining), Palestine, Syria (timber) and Nubia (gold) south of the first cataract. During the 2nd dynasty the center of gravity came to the north, where the kings’ tombs lay. Towards the end of the dynasty, increasing use of stone in architecture and art led to a first monumentality.

Old Kingdom (Dynasty 3–6, ca. 2700–2270 BC)

Often the dynasties came to change through mediation on the female side, which through inheritance law passed the line. Then the 3rd dynasty’s greatest pharaoh Djoser came to power. With him began a new era; he “opened the stone”. Djoser’s burial ground in Saqqara became the first truly monumental with an approximately 60 m high staircase pyramid in the center. The surrounding private tombs give us information about the growing administration, often consisting of royal relatives. Religious and profane offices were often combined; Djoser’s “vesir”, Imhotep, was a prominent example of this. Some more insignificant kings followed after Djoser, of whom Huni had built a fortress on the island of Elefantine at the southern border of the country.

During the 4th Dynasty, rural Egypt reached its prime flowering. There were no real wars, as organized opponents were missing, but the army carried out expeditions against Libyans and Nubians, and the trade relations by sea with Syria (Byblos) were also maintained. Egypt was not a distinct slave society; the great efforts that the pyramid builds entailed, first at Dahshur with the Snofrus pyramids and then at Giza with Cheops, the Heads of the Chief and Mykerino, may be regarded primarily as religiously founded works. The population lined up during the flood of the Nile, when farm work was largely down.

Such investments, and also other administration, required extensive administration, which now became an independent power factor. In addition, the religious sphere of power grew, which became apparent in the king’s ever greater dependence on the sun god (named “Res son”). The end of the Old Kingdom was characterized by a refined culture; art and literature experienced a glamorous period, while restructuring in society took place. The royal power was weakened, religious institutions gained more power, e.g. Re in Heliopolis, and large sun temples were built at Abusir. The civil service bureaucracy prospered, but power spread to several local centers; the county chiefs could no longer be controlled by the king. They established local dynasties, with their own residences, courts and tombs.

Among the new groups in the community, craftsmen, priests and civil servants at the local courts, there was the need for urbanization and the breeding ground for new religious tendencies. The Osirian cult grew, which is also reflected in the royal inscriptions, mainly the so-called pyramid texts in the kings’ tombs from the end of the 5th dynasty. We know the names of all kings but know little about individual historical events. The state trade, associated with looting trains, continued, and the first Red Sea expeditions to Punt (probably on the Somali coast) were made. Teti, the creator of the 6th dynasty, marries a royal daughter of the 5th dynasty. Pepi II, the last of the family, reigned 94 years.

First Intermediate Period (Dynasty 7-10, c. 2270-2040 BC)

During the 7th-8th dynasties a large number of kings appeared; however, real power had passed to the county chiefs, who gradually expanded their domains. During the 9th-10th dynasties, Herakleopolis in the middle and Thebes in southern Egypt were the most important centers. A century of internal strife ended with Thebes victory and the establishment of the new Egypt.

Middle Kingdom (Dynasty 11–13, c. 2040–1675 BC)

Pharaoh Mentuhotep I was the portal figure, during whose 51-year reign the newly unified Egypt was fortified from the Thebe residence. During the 11th and 12th dynasties, the country’s foreign relations came to flourish like never before. The gold assets in Nubia, which were increasingly coming under Egyptian control, were the country’s commercial political strength. 11th Dynasty’s last ruler Mentuhotep III fell victim to a coup d’état. Vesir Amenemhet seized power and began the 12th Dynasty. Thus the royal ideology was renewed; it was no longer based on the innate divinity of the ruler but on his power of deeds.

Amenemhood justified itself by referring to its war happiness and charity. He initiated a firm colonial policy against Nubia, which was continued by his son and successor Sesostris I. The borders were strengthened; the fortress in Buhen in Nubia was a big company, as were the border garrisons against the Asian and Libyan Bedouins. The residence was moved to the Memphis area, where the kings also built their graves (mainly at al-Lisht), some of the last pyramid buildings. With the exception of minor conflicts in Nubia and Palestine, the country was marked by peace and prosperity, exemplified by the cultivation of the Fayyumoa, a very significant achievement.

The king’s power was greatly strengthened during Sesostris III, which broke the power of the county chiefs. After Amenemhet IV, for the first time, a woman came to the throne, Sobeknofrure. The 13th dynasty constituted a perpetually rich period, a continuation of the cultural prosperity of the 12th dynasty, but the many short reigns could not assert the country’s integrity. Control over Nubia was lost, and in the north Asians gained a foothold.

Second Intermediate Period (Dynasty 14-17, c. 1675-1575 BC)

A lateral dynasty, the 14th, was founded in the Western Delta. The Pharaohs of the 13th Dynasty were confined to Upper Egypt. Asian ethnic groups formed the so-called hyksos (“the rulers of the foreign countries”). These created their own dynasties in Avaris (15th-16th) and claimed all of Egypt.

Some powerful Hyksos kings like Chian and Apopi successfully claimed themselves as Pharaohs and resumed, among other things. trade with Nubia, which detached itself from Egyptian control. With the hyksos, the horse, the chariot and the compound bow came to Egypt. At the same time, the Theban 17th Dynasty claimed the Pharaoh title. Seekenrere Taa II rebelled against Apopi but was killed. Kamose’s son continued and managed to defeat Hyksos. Brother Ahmose ended the fight and began the 18th dynasty.

New Kingdom (Dynasty 18–20, c. 1575–1087 BC)

Ahmose reached southern Palestine and returned to Nubia as a province, now with his own deputy king. An administration without county princes was built, Thebe became the capital and religious center. The son Amenhotep I was a great builder and founder of the Theban Tomb, whose patron he became.

From a sideline came the successor Thutmosis (Thothmes) I, who placed the military center of gravity on Memphis. He conquered and fortified southern Nubia. To the east, Thutmosis reached as far as the Euphrates, where he confronted the mighty Mitannic kingdom. He was the first to be buried in the Valley of the Kings in Thebes.

The son of Thutmosis II was married to his half-sister Hatschepsut. A son of Thutmosis II with a side goal became as minor Pharaoh Thutmosis III; Hatschepsut, however, took power himself. During her 20-year reign there was mainly peace; trade was extensive, from Punt to Crete. After her death, Thutmosis III erased the memory of her efforts and took the place himself as a legitimate ruler.

During a long reign, he emerged as the great warlord, trustee and organizer. Mitanni with allies threatened Egypt, prompting 17 campaigners to secure Egypt’s supremacy in Palestine and Syria; at Megiddo and Kadesh there were significant battles. Egypt became a great power that ruled the Ancient Orient and Nubia, now with the southern border at the fourth cataract. The kingdom was inherited by the son Amenhotep II. During Thutmosis IV, peace was achieved with Mitanni, threatened from the north by the Hittites. Egypt’s rule was maintained during Amenhotep III through gold deliveries to the Asian princes. During his time, the Hittites began to become a threat to Egypt.

The royal power was continually weakened during the 18th dynasty through Amun’s priesthood, which managed large land estates donated to the shrine in Karnak. The ideological contradiction between the conquest policy of the kings and the priests’ claim to power culminated under Amenhotep IV. He proclaimed the Sun album Aton as the only god, founded a new capital (Akhetaton) at Amarna, and erected a few years of Aton temples all over Egypt at the expense of other gods’ monuments, especially Amuns. Foreign policy was neglected and the Asian provinces were partially dissolved, but the danger to Egypt was not imminent because Mitanni played its role as a great power.

Akhenaton (Echnaton), named after Amenhotep IV after his religious revolution, was succeeded by his son-in-law Tutankhamun. A religious restoration was carried out and the country returned to old order. After Tutankhamun, the chief Eje took the role of Pharaoh, supported by General Horemheb, who in turn succeeded Eje. Horemheb moved the residence to Memphis and secured the garrisons in Syria and Nubia. With him ended the 18th dynasty.

During Horemheb, an officer and vesir named Paramessu served. Like Ramses I, he initiated a new dynasty. The son of Sethos I reaffirmed Egypt’s empire in Palestine, Lebanon and Syria. His son Ramses II reigned for 66 years. Ramses’ war against the Hittites was, despite large-scale, traditional-style victory reports on temple reliefs and inscriptions, lost. The Great Battle of Kadesh in 1285 largely ended in a draw, and the relationship with the Hittites was settled in a peace treaty in 1270.

The religious capital was still Thebe, where both Sethos I and Ramses II were responsible for the largest buildings since the time of the pyramids, especially in the Karnak Temple. In Nubia, Ramses II had the temple cut out at Abu Simbel. Pharaoh was now considered equal to the gods Amun, Re-Harakhte and Ptah and enjoyed special cult. In the delta (at Qantir) lay the residence, at which it is believed that Israel’s captive population worked.

During Ramses II ‘s successor Merenptah, the first attacks came from the so-called seafarers, while the Hittites no longer posed any threat. The dynasty was dissolved during internal battles.

The origin of the 20th dynasty is unknown. Pharaoh Sethnakht ruled only a few years, while his son Ramses III was the last great ruler of the New Kingdom. In 1180 and 1174 he won against the Libyans, 1177 against the seafarers. Egypt, however, was domestically in administrative and economic decay and could no longer assert itself as a trade political power. New factors came into play, including the lack of own iron production at a time when iron was the most important metal in the international market.

Ramses III was responsible for very large construction works, among others. the tomb temple in Thebe (Madinat Habu), which was also a palace and fortress. He was murdered by a conspiracy in 1153. During a long line of kings by the name of Ramses (IV – XI), Egypt went to dissolution, and local civil war broke out.

Third Intermediate Period (Dynasty 21–25, 1087–663 BC)

In Delta the real power was held by Smendes, founder of the 21st dynasty, while Amun’s high priest in Thebe, Herihor, founded a “god state” which, however, recognized Smendes; the two ruling groups maintained a good coexistence.

In Tanis, the kings of the 21st dynasty had their residence and their graves. Many Libyan rulers in the Delta had real power that the kings could not overlook, and Libyans from Bubastis emerged as Pharaohs of the 22nd Dynasty with Tanis as residence and tomb. Scheschonk I (945–924) was recognized by the Theban “god state,” and a son of him was made high priest there, which was put in the system by subsequent Libyan pharaohs. The royal house, however, came to be dissolved and divided into two branches. The 23rd and 24th dynasties consisted of rulers with little real power.

In the 7th century, the Cushitic kingdom at the Nile’s fourth cataract prevailed. With the capital Napata as the center, the black rulers there had created a kingdom with a pharaonic mark, they were worshipers of Amun and built tombs in pyramid form. Their prince Kashta gained some recognition in Egypt. His son Pianchi occupied Thebe and subdued Memphis and participated, where the Libyan princes recognized him. The successors Shabaka and Taharka were responsible for great construction, especially in Thebe.

In 671, the Assyrian king Assarhaddon attacked Egypt and captured Memphis. Two years later, the Assyrians returned, partially aided by Delta chiefs, but Taharka succeeded in regaining Memphis. In the year 667, however, Egypt was conquered by Assurbanipal, who inaugurated the sound king Necho in Sais. Taharka died in 664, and Necho’s son Psammetichos I (664-610) pursued the Cushites, who, however, still had influence in southern Egypt for some years.

Late times (dynasties 26-30, 663–343 BC)

The Saitian 26th Dynasty, with Psammetichos I as founder, ruled all over Egypt with Memphis as its capital. Time became a renaissance for the ancient pharaonic ideals, both ideologically and artistically. Egypt’s foreign policy supported Assyria in the fight against Babylon.

Necho II won supremacy over territories in Asia but lost them to Nebuchadnezzar. Psammetichos II eliminated the danger of the Cushites by marching towards Napata, after which they moved further south to a new seat, Meroe. Pharaoh Apries joined the covenant of Judah King Zedekia and Phoenician princes against Nebuchadnezzar. After mutiny in the army, General Amasis became Pharaoh in 570. He and his son Psammetichos III are included in the 26th dynasty.

Foreign relations showed new combinations; Greece became important politically and the Naukratis colony was founded in the Western Delta. Persia now became a great power against which Egypt was in alliance with Lydia, Babylon and Sparta. Under Cambysian leadership, the Persians attacked Egypt in 525. Amasis had just died, and Psammetichos III was captured.

Egypt during the 27th dynasty was a Persian satrapi. When Dareios II died in 404, a Libyan prince expelled the Persians. The 28th-30th dynasties ended Pharaonic Egypt. The last pharaoh, Nektanebos II, fled to Nubia when the Persians returned 343 during Artaxerxes III Ochos. Some, however, count the time until 332, when Alexander the Great conquered Egypt, as the 31st dynasty.

Ptolemy (305-30 BC)

When Alexander’s kingdom was dissolved, Egypt was taken over by General Ptolemy, who became king in 305. From that time, Egypt’s history is associated with Greek and later Roman and Byzantine history.

Ptolemy and his successors adapted to traditional royal ideology and iconography. The gods of Egypt continued to play a major role, especially Isis and Osiris as well as theological innovation Serapis. Large temples belonging to Egypt’s best preserved monuments (including in Dandara, Idfu and File) were erected under the Ptolemaic kings.

With Alexandria came a metropolis that was of great importance to science and culture. A number of Greek societies emerged, which, with their theaters, colleges, etc., constituted a whole new cultural element in the Pharaonic kingdom. Greek became the administrative language.

During the first Ptolemaic century, strong attempts were made to maintain dominion even in Syria and Asia Minor during conflicts with the keleukid kingdoms. Syria and Judea lapsed around 200 BC, Kyrene 98 and Cyprus 58 BC In the period after 200, the country was characterized by mutual quarrels, both within the royal house and locally. The Ptolemaic period ended when Cleopatra VII took his life when Octavian conquered Alexandria in 30 AD.

Roman and Byzantine times (30 BC – 640 AD)

Egypt became the Roman emperor’s own province. The royal ideology remained intact and temple construction continued. Alexandria continued to be of great importance, while the rest of the country was depleted. Egypt became Rome’s largest supplier of cereals and was an important link in the international route between India and Rome.

Greeks and Jews made their mark on Alexandria, and many unrest was caused by their power struggle. Egypt adopted Christianity very early, and the country became a hearth for many different theological schools. The first monasteries originated in Egypt, i.e. through Pachomios (dead 346) and Schenute (dead 466).

The Christian Coptic culture gained a distinctive character, since Egypt along with some other Eastern churches went their own way at the church meeting in Chalcedon 451. By then the Pharaonic temples had long since been closed or transformed into churches. In the sixth century, Egypt was conquered by the Persians during Khosru II, but these were expelled in 626 by the Byzantine emperor Herakleios. After 640, however, Egypt was definitely incorporated into the Arab world.

Period 640–1798: The Middle Ages of Egypt.

During the Great Islamic Conquest after Muhammad’s death (632), General Amr ibn al-As, at the head of a few thousand Arab riders, conquered Egypt from the Byzantine Empire. The occupation was carried out without strong opposition from the Christian population, the Copts, who were hostile to the Byzantine Empire not least for religious reasons. Like monophysites, they had been harassed by the Greek Orthodox Church, which paid tribute to the two-nature doctrine. The new Muslim rulers, on the other hand, did not interfere with people’s faith, both because Islam was in principle tolerant of other scriptural religions and because they were still too few to dominate.

The stage of Egypt’s history that began when the country was thus broken out of its context with the Roman-Greek-Christian world and ended when it was violently re-incorporated into a European power game, ie. 640-1798, can be called the Middle Ages of Egypt. It can, in turn, be divided into periods according to the headings below, after a series of shifts of power; however, formal and real power have far from always coincided.

Colony under the Caliphate (640–868).

During the first few centuries, when the governors of the Caliphs ruled Egypt from their Fustat camp (in present-day Cairo), the Arabic-speaking population grew steadily through the influx of soldiers from Asia and through the immigration of livestock tribes from Syria and Arabia. The Copts felt their positions threatened and made a series of rebellions, the last bloody blow about 830. It took several centuries before they became a minority, usually tolerated and financially influential, sometimes thwarted and persecuted. The Greek administrative language had been replaced by Arabic from the beginning; Gradually the Coptic was also removed as a vernacular and preserved only as the liturgical language of the Church. For half a millennium, Egypt had been transformed from a Hellenistic and Christian state to a core country in Islam.

Release under military governors (868–969).

After the political cohesion in Islam had broken, Egypt’s rulers began to increasingly oppose the Caliph in Baghdad in the 8th century. In 868, Turkish General Ahmad ibn Tulun stopped all tax payments to Baghdad and used Egypt’s resources to build a magnificent ruling city outside Fustat. Most famous of his buildings is the mosque that bears his name.

Independent superpower during the Fatimids (969–1171).

However, Cairo as the capital of the first truly independent Egypt since the time of the Pharaohs was a work of a new dynasty a hundred years later, the Fatimids. They had taken the name of Muhammad’s daughter Fatima and belonged to a radical phalanx, the Ismailites, within the Shi’a anti-Caliphate insurgency minority in Islam. During the 900s, they had submerged large parts of North Africa. From there, they conquered 969 Egypt and founded Cairo, with walls, gates, palaces and mosques, mainly among them al-Azhar, a mission center for their sect, soon also a renowned university. The Fatimids sought to conquer all of Islam and came quite close to the goal during the first century of the 1000s, when through their fleets they dominated the Mediterranean with islands such as Sicily, as well as Syria, Palestine and much of Arabia.

But the Ismailites never succeeded in winning either the Egyptians or the Muslims of Asia for their beliefs, which made their empire fragile. Attacks from seljuks in the east and from Christian crusaders further weakened the kingdom. Finally, the Fatimids faced the same fate as many former rulers in Egypt, overthrown by their mercenaries.

The Empire of the Ayyubids (1171–1250).

In 1171, the Kurdish Salah ad-Din al-Ayyubi (Saladin) took power in Egypt. He became one of Islam’s greatest heroes of all time as he withdrew Jerusalem from the Crusaders and struck back the Third Crusade. The Saladin-based Ayyubid dynasty restored the Sunni Orthodox in Egypt. The capital city of Cairo became the foremost trading city in Islam and al-Azhar its leading learning center. In many places in the kingdom, religious institutions for study and teaching (madrasa) were founded.

The costs of the many wars and the great construction activity forced the Ayyubids to donate large parts of Egypt’s land to the Kurdish and Turkish officers who, with their troops of slaves or released, were the mainstay of the regime. These so-called mamluks (mamluk = property, slave) became the country’s true masters; the peasants descended in impunity. The system became the fall of the dynasty. It was cleared out of the road in 1250 by a mammal closure.

The epidemic of mammals (1250-1517).

The long Mamluk night in Egypt was a military dictatorship, which, like previous regimes, could only exist through the constant influx of slave soldiers from the Asian countries of Islam. One of the first Mamluk rulers, Baybars, halted the 1260 Mongol storm, which had just hit Baghdad and ended the Abbasid caliphate. Abbasides took refuge in Cairo as a puppet caliph, thereby highlighting Egypt’s claim to leadership. The holy cities of Islam, Mecca and Medina, were also subject to the Mamluk Sultans. These launched an offensive south toward the still Christian Nubia. Large parts of Sudan became Muslim territory. During constant mutual feuds and under growing internal disarray, which went beyond the free peasants, the fellaher, the Mamluks transformed Egypt into a private domain.

In the 15th century, however, Persia began to again compete with Egypt for its position as an intermediary in the east-west trade. Economic decline and growing disarray with protracted mutual feuds made Egypt ripe for a new conquest. In Asia Minor and the Balkan Peninsula, the Turkish Ottomans had built up a great kingdom. At the beginning of the 16th century, their Sultan Selim I initiated the conquest of the Ancient Orient. In 1517, Egypt was incorporated into the Ottoman Empire.

The Empire of the Ottomans (1517–1798)

For a short time, the Ottoman conquest brought about a stir. Egypt regained its positions in international trade. The Ottomans tried to improve the position of the Fellows through reforms. But within a few decades, the decay began again. The Ottoman Viceroy (vali or pascha) lost control of the administration and the economy. The Mamluks took the reins again. They were in control of the local administration and again laid down most of the land, which they raised through taxpayers (often Copts) the state income, which largely stayed in the pockets of mamluk. Among them, they fought as before, most devastatingly in the 18th century. During this, the irrigation facilities were neglected and the desert advanced. Infiltration of Bedouins from the other side of the Red Sea contributed to the pressure of the Fellows.

From 1798: new era.

When Egypt was brutally moved into Europe’s politics at the end of the 18th century, with devastating consequences for all its conditions, a new era began in the history of Egypt. Napoleon invaded the country as part of the fight against Britain. The occupation was a brief episode, but when the French evacuated the country they left behind schools and hospitals, scientific institutions, improved communications, sketches for modernized government and seeds for a national Egyptian reaction to foreigners’ multi-millennial dominance in the country.

Modernization policy under Muhammad Ali and his family (1805–82)

During the continuing war between British, Ottomans and Mamluks, he inherited a new foreign dynasty as heir to the French reform program. The Macedonian officer Muhammad Ali, supported by his Albanian troops, swung himself up to the Viceroy (1805) and, six years later, finally ended the Mamluk era when, after a party at the Citadel in Cairo, he killed 500 of their leaders.

Muhammad Ali wanted to assert his independence from the Sultan of Istanbul, as well as Europe’s great powers, and make Egypt the leading power of Islam. To this end, he sought to build a modern army based on European model, which in turn required administrative and economic reforms. The feudal soil structure was vigorously attacked; the state, that is, the paschan itself, became, at least in principle, the owner of the land. Cotton was cultivated in the state domains, which became Egypt’s most important export commodity. Textile and military industries, including state monopolies, were set up. The cadre of all necessary military, technical and administrative officials and officials was obtained by importing experts from Europe, preferably France,

Muhammad Ali led an expansive foreign policy. In the 1820s, he conquered Kurdufan in northern Sudan, not least in order to fill his armies with Sudanese slaves. When things went wrong, he recruited soldiers among the Egyptian peasants. It was the first time in millennia that Egypt contained anything but foreign troops. Paschan also waged war in Arabia and was close to conquering Syria. But the European superpowers, especially Britain, did not want any strong power in the Middle East and forced him to return his conquests to the Sultan. His state operation of Egypt was in conflict with European trade interests. At that point, too, he must retreat and open the Egyptian market. Soon the Egyptian textile industry was out-competed by Europeans, and Egypt became the predominant raw material supplier. The state monopoly on land was loosened up when Muhammad Ali to finance war and industrialization had to give land in loan to high officials and to members of his own large family. When he abdicated in 1848 (he died the following year) and succeeded by sons and grandsons (Ibrahim Pasha 1848, Abbas In 1848, Said 1854, Ismail Pasha 1863), all with inferior political capacity, it became clear that many of the modernization efforts had failed and that Egypt, contrary to Pasch’s intentions, had become economically dependent on Europe. But Egypt’s population had increased from perhaps 2½ to 4½ million, the cultivation area and trade had increased even more and an Egyptian-educated elite emerged as a counterweight to the dominant Turks and Europeans.

The European influence on the economy grew continuously. In the 1850s, the British got a concession on a railway between Cairo and Suez. In 1854, Ferdinand de Lesseps began to build a channel between the Mediterranean and the Red Sea. It was inaugurated in 1869, signified enough by the French Empress Eugénie. The Suez Canal made Egypt an even more desirable replacement in the ongoing imperialist struggle for power and markets. It helped Egypt’s foreign debt burden grow avalanche. Huge amounts of day jobs had been taken out by the fellaher at the canal building, to the detriment of agriculture.

Under Ismail’s government, the financial situation developed into a crisis. He had the ambition to Europeanise Egypt and free it from all dependence on Turkey. By the Sultan, he succeeded – for a high fee – to develop succession rights for his branch of the dynasty and the more noble title Kediv. He threw himself into a costly expansionary policy in Sudan. Under British officers such as Samuel White Baker and Charles Gordon, Egyptian troops pushed all the way down to Lake Victoria in Central Africa. In the west, Darfur was conquered, ports were acquired on the Red Sea and on the Somali coast.

At the same time, the Kedives pursued a modernization policy, which was mainly aimed at strengthening the infrastructure: railways, telegraph lines, irrigation canals, bridges and port facilities. Egypt’s state income and exports also increased significantly, but so did the debt burden. Ismail had taken over a debt of £ 7 million; in the 1870s it reached close to 100 million. During the American Civil War, Egypt’s cotton exports flourished, but after 1865 the setback came. It did not help that Ismail sold its shares in the Channel Company to the United Kingdom (1875). Shortly thereafter, the foreign creditors forced Egypt to place its debts under international management and the entire financial system under French-British control. Kediven must also share power with a government minister, where a British and a French minister sat on key posts.

Ismail made one last attempt to assert its position. He could, to some extent, rely on the advisory congregation with representatives from the villages he set up himself and on xenophobic attitudes within the army – often however as much aimed at the Turk as the Europeans. But in 1879 the superpowers persuaded the Sultan to oust him. Against Ismail’s successor Tawfiq, a national uprising broke out. The leader, Colonel Urabi Pasha, called himself “the Egyptian” and launched the slogan “Egypt for the Egyptians”. Tawfiq called France and Britain to help, and the British took the chance. A British fleet bombed Alexandria, British troops struck Urabi’s army. The whole country was occupied in 1882.

British Occupation (1882-1922, real until 1952)

The old governing body was maintained during the British occupation, but the real ruler became the British “agent”, Evelyn Baring Cromer. His patriarchal and frugal government for nearly a quarter of a century put Egypt on its feet, reformed its administration, and to some extent improved the position of the Fella Lords, all with the help of a growing body of British officials, often with experience from India of how natives would be treated and nurtured. The Kedives, especially Abbas II, tried unsuccessfully to oppose Cromer.

When the World War broke out in 1914, the informal patronage of Egypt was transformed into a formal one. The economic consequences of the war brought renewed nourishment for the Egyptian nationalists, who were, however, divided into a Western-oriented middle-class falang and fundamentalist Muslim movements among the masses. The leadership of the previous direction, which loudly demanded the independence of Egypt, was taken by Sad Zaghlul, Egyptian farmer, lawyer and politician. He was deported by the British but released after a while. In 1920 he negotiated in London on Egypt’s recognition as a sovereign state, and in February 1922 the country became a kingdom under Fuad I. But when Britain ruled Sudan and the canal zone, the real power stayed with the British.

In the first elections under the new constitution (1924), the Wafd Party won the leadership of Zaghlul. His politics, on the one hand, focused on the king and the Turkish overlord, on the other against the British. In this way, Egyptian politics became a triangle drama. An agreement was reached in 1936 to gradually evacuate the British troops from the canal zone. But World War II came in between. The Wafd Party supported the British war effort, which cost a large part of its popular support. Anti-Western, religious Orthodox and Arab-national movements, mainly the Muslim Brotherhood, gained growing influence after 1945. Egypt was active in the founding of the Arab League in 1945., whose headquarters were located in Cairo. In May 1948, troops from Egypt, Transjordan, Syria, Iraq and Lebanon invaded the newly established Israel in the so-called Palestine War. It ended with Israeli land enlargement, but at the standstill (1949) Egypt retained the Gaza Strip.

Arab Republic (1953–2012)

Neither political parties nor religious organizations took home the game in the internal power struggle. In 1952, a revolutionary group, the Free Officers, conducted a coup d’état under Gamal Abdel Nasser. King Faruq was deposed, and in 1953 Egypt became a socialist and Muslim Arab republic with General Mohammed Naguib as president. He was replaced in 1956 by Nasser. Basically it was a military dictatorship. Nasser inherited many former Egyptian greatness dreams. He wanted to become the entire Arab world, the whole of Africa, the whole of Islam. One step in that direction was the union with Syria, the United Arab Republic, which lasted for only three years (1958-61).

In Egypt, Nasser wanted to stabilize its board by giving the rapidly growing population more tolerable conditions. A land reform, which limited individual land ownership to 100 ha – later less – was proclaimed. But the cornerstone of this policy was a huge dam construction at Assuan, which would provide Egypt with new agricultural land and energy for industrialization. When the Western world refused him a loan for that purpose, he turned to the Soviet Union and nationalized the Suez Canal in 1956. Britain, in alliance with France and Israel, intervened in arms power but was allowed to cancel the campaign under pressure from the US and the Soviet Union. Nasser triumphed. His position was briefly shaken by yet another unfortunate war against Israel in 1967 (the Six Day War). But the Assuan dam (The High Pond) was completed in 1970, the same year that Nasser died as one of his country’s and Arab’s heroes.

The successor Anwar as-Sadat, one of the officers from 1952, was more moderate in domestic and foreign policy. Admittedly, in 1973 he staged the October War (Yom Kippur War) lost to Israel, but then entered into negotiations (see Camp David Accords) and made peace with Israel in 1979, with Egypt regaining Sinai, lost in the Six Day War. The settlement with the arch-enemy incited him to the hatred of the other Arab states and the domestic opposition. He was murdered in 1981 by fanatics during a troop row. Egypt was excluded from the Arab League, whose headquarters were moved to Tunis.

President again became an officer, Hosni Mubarak. He pursued peace policy and at the same time succeeded in reconnecting with several Arab states; Egypt has been a member of the Arab League since 1989. Mubarak, too, fought against Muslim fundamentalists and other opposition, but above all against pressing economic problems in the impoverished eighty million state. During Mubarak’s time in power, steps were taken towards civilian and more democratic governance, but even though some political opposition was tolerated, the president made sure that his own position of power remained unharmed. The state of emergency introduced after the murder of Sadat was never abolished by Mubarak, but was extended one by one. The number of terrorist acts against leading politicians, security forces, foreign tourists and Christian Egyptians (Copts) increased.

Egypt was strongly involved on the UN side in the Kuwaiti crisis and the 1990-191 war. Relations with many Arab states, especially Syria, were thereby improved, as was Egypt’s negotiating position with the Western creditors. The country was in dire need of financial relief, as the war caused a major disruption to tourism and forced many Egyptian guest workers to return from Kuwait and Saudi Arabia to Egypt, which already had an unemployment rate of over 20 percent. Despite good average economic growth in recent decades, a large part of Egyptians are still living in poverty. Instead of the state, among other things, the Muslim Brotherhood is taking over and other more radical Islamist movements enter and engage in social work with their own schools and health clinics. The Muslim Brotherhood, for a long time the most important opposition force in the country, has officially been banned, but has nevertheless been allowed to operate.

Following the September 11 attacks in 2001, Egypt declared that it would cooperate with the United States in the investigation, but did not contribute troops in the war on terror. The fact that the Mubarak regime was one of the United States’ most important allies in the Middle East caused great dissatisfaction within the country. The president was also criticized for what he saw as his attempt to bring his son Gamal forward as his successor.

In the 2005 presidential election, for the first time, other candidates were allowed to stand against Mubarak, who has so far been approved four times in referendums without counter-candidates. However, the nine other candidates failed to mobilize sufficient resistance and Mubarak was re-elected with 89 percent of the vote. Although the opposition was harassed in various ways, candidates loyal to the Muslim Brotherhood got about 20 percent of the mandate in the parliamentary elections that year. Voting was low on both occasions; just under one in four voters participated. The opposition’s success led to increased political repression in the coming years.

From 2009, the opposition grew in strength when the Mayhkomsh campaign (about ‘he should not rule’) was launched. In addition to the opposition party al-Ghad (“Morning Day”) included the Muslim Brotherhood and the Facebook-based April 6 movement. Peace Prize laureate and former Director General of the International Nuclear Energy Agency (IAEA) Mohamed ElBaradei formed ahead of the 2010 parliamentary elections The National Coalition for Change but, like al-Ghad, the coalition eventually chose to boycott the election, preceded by harassment targeting the opposition; Among other things, about 1,000 members of the Muslim Brotherhood were arrested.

After several years without major terrorist acts, a large number of tourists were killed in attacks during both 2004 and 2005. Three almost simultaneous bomb attacks in the tourist resort of Sharm ash-Shaykh in July 2005 took at least 88 people’s lives. A ship accident in the Red Sea the following year cost more than 1,300 people. In addition to the political tensions within the country, widespread police brutality, persecution of the Copts (the country’s Christian minority), violence against African migrants traveling through the country, and the sexual harassment suffered by most Egyptian women were also reported in the 00s.

National uprising, power vacuum and new military rule (since 2012)

Inspired by the so-called Jasmine Revolution in Tunisia, in January 2011, large crowds gathered at the Tahrir Square in Cairo to demonstrate against the regime (compare Arab Spring). Despite attempts by the authorities to stop the protests, both by violent police action and by shutting down the internet and mobile phone traffic, the revolt continued, not only at Tahrir Square but elsewhere in the country. The powerful military chose to remain neutral and on February 11, Mubarak handed over power to a military council headed by Field Marshal Hussein Tantawi. In June 2012, Mubarak was sentenced to life imprisonment for failing to stop the violence that took about 850 people’s lives in connection with the uprising against his regime; he appealed and was released in 2017.

The protesters, who were united about the goal of deposing Mubarak, turned out to have different perceptions about which society would instead be built. In the parliamentary elections held between November 2011 and February 2012, the Islamists reaped great success, not only the moderate Muslim Brotherhood’s Party of Freedom and Justice but also the strictly conservative Islamist party al-Nur (‘the light’), dominated by literate Salafists. This caused concern among the many young and Western-inspired people who were driving during the revolution, especially at the beginning of the same.

The military council was already accused in the spring of 2011 of clinging to power and demonstrations again took place at Tahrir Square, but these were beaten down with force. Deadly attacks on Copts increased after Mubarak’s fall. In February 2012, 74 people were killed in connection with a football match in Port Said. The unrest hit many Egyptians financially, not least those who depended on tourism for their livelihood; the number of foreign tourists fell sharply in 2011.

In the spring of 2012, it turned out that the struggle for power, mainly symbolized by the presidential post, stood between the Islamists and representatives of the old regime with close ties to the military. In June 2012, the Military Council dissolved the Islamist-dominated parliament, citing the Constitutional Court’s failure to approve the election. The presidential election, held in May-June of the same year, became a struggle between the leader of the Freedom and Justice Party Muhammad Mursi and Ahmed Shafiq, former Air Force Chief and Air Minister and Mubarak’s last Prime Minister. In the end, it turned out that Mursi won a tight victory with 52 percent of the vote. Mursi’s membership in the Muslim Brotherhood ended after the election victory.

In June 2012, the state of emergency that had expired since 1981 expired without, as several times before, being extended. In August, a border post was attacked between Egypt and the Gaza Strip and 16 Egyptian soldiers were killed. After another attack, several high-ranking soldiers were fired, including Tantawi being fired as army chief and defense minister. Mursi also repealed the June declaration giving the military council the legislative power.

However, dissatisfaction with the president grew ever stronger. Violent protests erupted since Mursi issued a decree in November that gave him extensive powers and also deprived the judiciary of the opportunity to stop his decision. The situation, with tens of thousands of protesters at Tahrir Square, was similar to that when Mubarak was overthrown. The following month, Mursi withdrew his decree.

The Islamist-dominated Constituent Assembly, which was commissioned to draft a new constitution, approved a constitutional proposal in November. The meeting was boycotted by the liberal, secular and Christian members. The constitutional proposal was criticized for being too Islamic and not sufficiently respecting human rights. With 64 per cent of the votes, the new constitution was approved in a referendum, but only 33 percent of the eligible voters participated.

The discontent against President Mursi continued and in connection with the two-year anniversary of the rebellion against Mubarak, hundreds of thousands of people protested at Tahrir Square and elsewhere, accusing the new regime of betraying the revolution. In connection with the demonstrations, hundreds of cases were reported in which women were subjected to sexual harassment and abuse of groups of men. Similar incidents have occurred both earlier and later.

The protests against Mursi reached their peak in the summer of 2013. Enormous crowds demonstrated from June 30 in Cairo and elsewhere in Egypt. After four days of mounting protests, the military led a coup d’etat and on July 3, Mursi was dismissed from the presidential post. As acting President, the President of Egypt’s Constitutional Court, Adli Mansour, was appointed.

In reality, however, the country’s highest ruler was the army chief and Defense Minister Abd al-Fattah al-Sisi. He enjoyed great confidence in large sections of the population, but the followers of Mursi and the Muslim Brotherhood filled streets and squares in Cairo and demanded that Mursi be reinstated. The new regime chose to disperse two protest camps in Cairo by force, and during the second half of 2013, several thousand protesters were killed and many more were imprisoned, including Mursi and most of the Muslim Brotherhood’s leadership. The organization itself was terrorist-stamped and banned. Since then, mass trials against supporters of the Muslim Brotherhood have been held and several hundred people, including Mursi, have been sentenced to death.

Proposals for constitutional amendments were drafted in the fall of 2013 and approved by 98 percent of voters in a referendum in January 2014. However, as in the May presidential election, turnout was low, below 50 percent. This was largely due to the Muslim Brotherhood calling for boycotts. In the presidential election, al-Sisi was waiting. Without real challengers, he won 97 percent of the vote. He received an equal share of the votes in the 2018 election, when again there were no serious candidates. On both occasions, turnout was below 50 percent.

al-Sisi’s regime has been criticized both in Egypt and internationally for the lack of human rights in the country. Economic stagnation and increased cost of living due to high inflation have in recent years caused dissatisfaction among parts of the population.

Historical overview

| 10000 BC – 5000 | The younger Stone Age: refined flint implements, beginnings of arable farming, especially in northern Egypt. | |

| 6000-4500 | The Merimde culture in the southwest participated as the main exponent of arable agricultural culture. | |

| 3000 | Minor chiefdom merges into two major power blocks in the north (Lower Egypt) and the south (Upper Egypt). Princes from the south conquer the delta and create “The Two Countries”. The script is invented. |

|

| 2700 | The Third Dynasty and Pharaoh Djoser consolidate the country. | |

| 2600-2500 | The time of the great pyramid builders. | |

| 2500-2100 | The royal power is weakened, the provincial princes form their own courts. | |

| 2100-2000 | The Theban princes unite the country again. | |

| 2000-1675 | The 12th Dynasty significantly expands Egypt’s borders, colonization policy in Nubia and Asia Minor. Inner colonization in Fayyum. The county chiefs are of little importance. | |

| 1675-1575 | Asians, so-called hyksos, gain significant control over Egypt. They proclaim themselves Pharaohs. | |

| 1575-1087 | Ahmose drives out hyksos. Queen Hatschepsut reigns during Thutmosis III’s minority. This extends the borders of Egypt to the south and east. During Amenhotep IV (Akhenaton), a religious transformation takes place, when the king launches the solar album Aton as the only god. Ramses II tries to subvert the Hittites in the Battle of Kadesh. During Ramses III major attacks against the so-called seafarers. |

|

| 1087-663 | A cleric is founded in Thebe, which recognizes pharaohs in the delta. Libyans will be pharaohs, as will later coastal Hits from Sudan, 25th dynasty. | |

| 664-343 | After Assyrian conquest of the country, a new dynasty is established in Sais. A cultural heyday. In 525 Egypt is conquered by the Persians, who are expelled 404. They return 343. | |

| 332 | Egypt is conquered by Alexander the Great. | |

| 305 | The country becomes a kingdom under Ptolemy I. | |

| 30 | Egypt is annexed by the Romans and becomes the emperor’s private colony. | |

| 130 AD | Hadrian visits Egypt (and founded Antinoopolis). | |

| 180 | The first Christian school is founded in Alexandria. | |

| 268 | Queen Zenobia of Palmyra invades Delta. | |

| 395 | The old temples are closed; Egypt becomes a Christian country. | |

| 451 | Church Meeting in Chalcedon: Egypt will in the future belong to a small group of Eastern churches with a special attitude to the divine status of Christ. | |

| 619 | The Sasanid Persians conquer Egypt. | |

| 626 | Byzantine emperor Herakleios is returning the country. | |

| 639-641 | Arab riders conquer Egypt from the Byzantine empire. | |

| 868 | Ahmad ibn Tulun makes Egypt truly independent of the Caliph in Baghdad. | |

| 969 | The Fatimids conquer Egypt and establish Cairo as the capital. | |

| 1171 | The Fatimids are overthrown by Salah ad-Din al-Ayyubi, who strikes back the Third Crusade. | |

| 1250 | Mamluker overthrows the Ayyubids. | |

| 1260 | Sultan Baybars I hit back the Mongol storm. | |

| 1517 | The Ottomans under Selim I invade Egypt. | |

| 1700s | Mamluker makes Egypt truly free from the Ottomans. | |

| 1798 | Bonaparte conquers Egypt. | |

| 1800 | The French evacuate Egypt. | |

| 1805 | Muhammad Ali is proclaimed Deputy King. | |

| 1811 | Mamluk night is finally crushed. | |

| 1854 | Lesseps gets a concession on digging a canal through the Suez lake. | |

| 1869 | The channels are opened. | |

| 1879 | Kediv Ismail is set aside after pressure from the major powers. | |

| 1882 | The British occupy Egypt; Lord Cromer becomes the real ruler. | |

| 1914 | Egypt formally becomes British protectorate. | |

| 1922 | Egypt becomes a kingdom. | |

| 1936 | Anglo-Egyptian agreement on the gradual withdrawal of British forces; World War II prevents enforcement. | |

| 1948-49 | Egypt participates in the Palestinian war. | |

| 1952 | “Free officers” overthrow King Faruq and abolish the kingdom. | |

| 1956 | Nasser becomes president, nationalizing the Suez Canal to fund a new Assuand dam. British-French-Israeli attack on Egypt is suspended under pressure from the great powers. | |

| 1967 | Egypt participates in the Six Day War. | |

| 1970 | Nasser dies. | |

| 1973 | Egypt participates in the October War (Yom Kippur War). | |

| 1979 | Peace between Egypt and Israel. | |

| 1981 | Sadat is murdered and replaced at the presidential post by Hosni Mubarak. | |

| 1997 | Islamic terrorists kill 58 tourists in Luxor. | |

| 2005 | 88 people are killed in blast attacks in Sharm ash-Shaykh. | |

| 2011 | President Mubarak is forced to step down after major demonstrations. | |

| 2012 | Muhammad Mursi wins Egypt’s first free presidential election. | |

| 2013 | Mursi is overthrown and thousands of people are killed or arrested in the protests that follow. Army chief Abd al-Fattah al-Sisi, who was one of the leaders in the coup, is elected new president. |