Poland is a country located in Central Europe and bordered by Germany to the west, the Czech Republic and Slovakia to the south, Ukraine and Belarus to the east, and Lithuania and The Kaliningrad Oblast of Russia to the north. According to homosociety, it has a population of around 38 million people, making it one of the most populous countries in Europe. Poland has a rich cultural history with many art, music, literature and architectural influences from its past. The capital city of Warsaw is home to many historical sites as well as museums showcasing art from around the world. Poland is also known for its diverse landscape with mountains, lakes and forests providing plenty of opportunities for outdoor activities like hiking and skiing. The economy of Poland is largely based on industry with major sectors being automotive production, electronics production, pharmaceuticals production, food processing and tourism. Poland is also an important member of both NATO and the European Union.

Prehistory

Between the ice ages, the memorial and the rice, perhaps more than 350,000 years ago, lived Neanderthal people in southern Poland. From about 130,000 years ago, there are several traces of settlement in caves, among other things. near Cracow, and from a cave near Zakopane comes a boomerang of mammoth bones, dated to 25,000 BC During the Late Paleolithic (c. 40,000–10,000 BC), central Poland’s then tundra landscape was populated; from about 14,000 BC reindeer hunters moved further north and east. Gift exchanges between people in southern Poland and western Europe can be discerned during the gastro-valley (about 16,000-10,000 BC). Later, Mesolithic settlements are known from all over the country; On the coast there was some exchange of gifts with Southern Scandinavia.

From about 4500 BC The Neolithic peasant age seems to have started: in the fertile loose soil areas in the south, there are traces of communities with longhouses for 5–6 families and with wheat and rye cultivation and livestock management as the main industries. In the lowlands a slow neolithic process is visible; remnants include tall piles, long, trapezoidal houses and flint mines (eg in Góry Świętokrzyskie). See abbreviationfinder for geography, history, society, politics, and economy of Poland. From central Poland mass burials of people and animals are known and from individual south burials (Złota, Sandọmierz). In eastern Poland there were neolithic trapping cultures.

Metal objects existed during the Neolithic period but occurred during the Bronze Age (c. 2000–700 BC) to an increasing extent. From about 1200 BC settlements were often surrounded by palisades and ramparts, and victims of metal objects in wetlands and rivers occurred. Bronze production gradually became more homogeneous and contacts with southern Scandinavia increased; in such contacts between different social networks, the exchange of amber and salt played a crucial role. The increasing complexity of society is indicated by variations in the religious symbolism (sun symbols, animal figures, etc.). The dead were burned and buried in urns on expansive flatmark tomb fields (compare the Lutzitz culture).

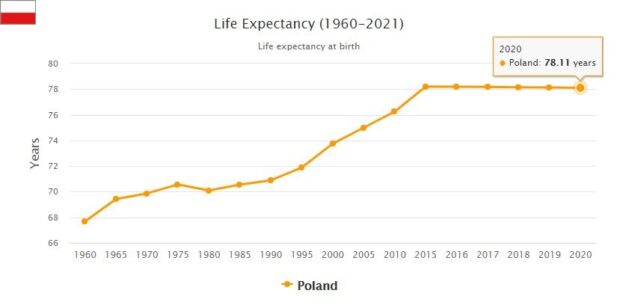

- COUNTRYAAH.COM: Provides latest population data about Poland. Lists by Year from 1950 to 2020. Also includes major cities by population.

From the Iron Age (700 BC to 400 AD), many tombs and settlements are known. In the south, a Scythian influence is noticeable, in Pomerania occurred from about 600 BC. stone coffins (often with facial urns) and in eastern Poland there are tomb fields and pile-building settlements. The introduction of community organization, local iron production and changes in the cultivation system contributed to the growth of centers with wide trade links; import finds from about 120 BC to the 300s AD includes coins, objects of gold, silver and glass as well as bronze wine cups and silks from the Roman Empire. From Poland, for example, amber, and transit trade between Italy and Northern Europe went, among other things. via Wisła.

From the 14th century, the centers of iron production in Góry Świętokrzyskie, increasing agricultural specialization and trade contacts with France, Scandinavia and Russia contributed to the consolidation of communities in central Poland. Scandinavian contacts are visible in early medieval trading centers from the 600–800s such as Truso (near Elbląg) and Wolin. The growth of the Polish state at the end of the 9th century is acknowledged, among other things. by Ostrów Lednicki, a princely castle with church and city-like buildings on a lake in northern Poland.

History

The Polish state has undergone major changes over time, and the boundaries have many times shifted. From being a mighty kingdom that stretched from the Baltic to the Black Sea in the late Middle Ages, the country was divided by long-standing internal disintegration between the neighboring states of Russia, Austria and Prussia at the end of the 18th century. When the imperial empires at the end of the First World War dissolved, Poland was re-established as a republic. Created at the expense of the great powers of Russia and Germany, but also with its own superpower dreams and with disputed borders to smaller neighbors such as Lithuania and Czechoslovakia, Poland has also suffered dramatic conversions during the 20th century.

Piast Dynasty (960s – 1370)

The name Polska (Poland) was adopted in the 9th century in an area around the present Poznań. It was inhabited by the West Slavic Poles, who were one of the many Slavic, Celtic, Baltic and Germanic tribes living within the vast plains east of the Oder (Greater Poland) which forms the central part of modern Poland. How the Poles acquired a dominant position in the ethnically diverse area is obscured.

Poland’s political history is usually considered to begin in the 960s with Duke Mieszko I of the Piast family, who, according to the Chronicles, organized the empire by conquering the Baltic coastal areas with its rich trading locations, establishing international relations and adopting Roman Christianity in 966. A bishopric was established in 968.

Kraków, located in the rule of Czech princes in southern Poland (the Lesser Poland), was annexed after Mieszko’s marriage with a Czech princess to the Greater Poland and soon grew into a political center of power. Elder son Boleslav I, who with papal approval was crowned Poland’s first king in 1025, moved in competition with the German-Roman Empire of Poland far beyond the ethnic boundaries of the Polish tribes. He established an archbishopric in Gniezno in 1000, giving Poland a place in the Western cultural sphere.

Domestic politics, a feudal nobility strengthened its power, and from the early 1100s Poland was divided into a large number of regional principals in the Greater Poland, the Lesser Poland, Kujawia, Masovia and Silesia, whose masters fought for power over Kraków. In the Silesian and Pomeranian border areas in the west, the Poles quarreled with a German warrior class about the dominion, and in the Baltic area with German knights. In the east, both the Mongols and the Lithuanians from the 1240s posed constant threats to the Lesser Polish and Masovian princes. The only unifying link was the Catholic Church.

A period of both external expansion and inner collection took place after 1320. German pressure against the western border and a power vacuum in the Slavic areas in the east following the ravages of the Mongols made an eastern expansion direction natural. Kasimir IIIThe conquest of areas in the southeast in the mid-1300s gave Poland control over the waterways to the Black Sea. Kasimir, the last king of Piastetten, consolidated both kingdoms and state power, the latter by homogenizing the judiciary, appointing regionally responsible governors, building fortified cities, and encouraging German and Dutch immigration and cultivating previously unspoilt areas. In Krakow, a university was created in 1364, which received an international mark. At a time when Jews were to blame for the ravages of poaching death elsewhere in Europe, they were given a sanctuary in Poland.

The Jagelons and the Staff Union (1370–1572)

After the death of Kasimir III, the royal power passed to his sister, the Hungarian king Louis I, then with the consent of the Polish aristocracy to his daughter Hedvig (Polish Jadwiga), crowned in Kraków 1384. Faced with the prospect of expanding Polish territory and protecting it from invasions from the Mongols and the German Order, the nobility was likewise well disposed to the marriage between Hedvig and the Lithuanian Grand Duke Jagiello (King 1386 under the name of Vladislav II) which took place in 1385 and founded a staff union between Poland and Lithuania.

The Grand Duchy had a territory four times larger than Poland, including cities such as Kiev and Smolensk, and partly pagan and partly Orthodox. The dynastic association brought about dramatic changes, especially in the Lithuanian region. Based on a newly established bishopric in Vilnius, the population was baptized together with Jagiello. Lithuania became Catholic and the Lithuanian Bojarat noble was polarized.

The political, economic and cultural upswing that began during Kasimir III also continued during the reign of the Jagelons. The Samogitia was introduced into the state after the decisive defeat of the German Order at the Battle of Tannenberg in 1410, and a successful war against the Order Knights 1454–66 restored Poland’s influence over the Pomeranian and Prussian Baltic areas. However, when the threat from the state of disintegration ceased, new enemies stood in line at the Polish borders: mosques, Ottomans and Crimean Tatars.

The many wars left traces in domestic political and social development. The royal power became increasingly dependent on the services of the feudal nobility, which from the 15th century afforded these opportunities to demand increased political influence and privileges such as tax exemption. In 1493, for the first time, a noble congregation, the Sejm, met to assert the nobility’s interests against the royal power. The rest of the population was severely affected by the tax burdens imposed by the war through the noble privileges. The peasants were at the same time driven by various statutes into life traits and social misery.

In economic terms, the 16th century was a Polish golden age. Enthusiastic nobles started large-scale production of grain for an international market, products shipped via the free, German-dominated trading town of Danzig (Polish Gdańsk). During the Jagelons a Polish-language literature was created, and the Polish Nicolaus Copernicus contributed his revolutionary theory of the earth’s movement around the sun to a great extent to the scientific progress of the Renaissance. In Poland, where various religious groups have long lived in consensus, it was consequently true that the Reformation also gained limited entrance, especially among the German urban population. Calvinism found many followers among Polish nobles, and in eastern Poland the prevailing Catholicism was challenged by innovative Orthodox so-called brotherhood.

Nobility Republic (1569–1795)

Polish and Lithuanian noblemen, who feared growing internal divisions and external threats, decided in Lublin in 1569 to transform the personnel union between Poland and Lithuania into a real union, where each part would retain its respective laws and administrations but be governed by a common, elected king and sejm. To mark the king’s submission to the unified nobility, szlachta, the real- life union Rzeczpospolita (‘the Republic’) was named, and Warsaw became a new capital. After the death of the last Jagelon king in 1572, Poland became an electoral kingdom, in which the king soon became the president. Religious tolerance was guaranteed by law.

However, Adeln’s hopes that a real union could work together came to shame. From the end of the 16th century, on the contrary, a process of fragmentation and weakening took place, which manifested itself in foreign political adversities, internal political chaos, increased social tensions and religious contradictions. The many dynastic wars of dominion over the Baltic Sea area, from the Lifelong War of 1558–83 to the Great Nordic War of 1700–21, exhausted Poland’s resources. Recurring military conflicts against Russia, Sweden (see Polish-Swedish War) and the Ottoman Empire led to major territorial losses on the Baltic Sea and the East.

History research has in particular traced the foreign policy problems to Vasakungen Johan II Kasimir’s reign 1648–68, when Poland was forced to give up parts of eastern territory (Ukraine) after a Cossack rebellion in 1648–54 and Prussia 1657. In addition, parts of Poland were occupied by Sweden in 1655– 57th Frederica in Oliwa 1660 and Andrussovo 1667 with Sweden and Russia respectively suffered minor land losses. In Oliwa, Poland was forced to write off the claims on the Swedish krona that have been claimed since the Swedish revolt in the 1590s against Sigismund III, son of Johan III of Sweden and his Polish wife Katarina Jagellonica. When Poland in addition under Johan IIISobieski’s reign in 1674–96 was forced to face a Turkish expansion from the south, completely exhausted the country’s military resources. During the Great Nordic War, Poland was severely devastated, especially by the Swedish troops who used Poland as a base during the first half of the war. The ruined country was transformed into a Russian protectorate after the war.

The numerous wars tore apart the area’s economic infrastructure and contributed to the rapid decline of the Baltic Sea trade after 1650. Many noblemen in the numerous Szlachta group lost their wealth, while individual aristocrats from powerful families such as Radziwiłł, Potocki and Czartoryski were still able to gain large built on living property, large estates and create their own self-sufficient territories within Poland.

The widening social divisions within the nobility and between landowners and the living increased significantly the internal turmoil, but also the political fragmentation, as the magnates, through bribery and client relationships, could build their own power groups in the sejm. Since the so-called liberal veto was applied for the first time in 1652, the sejm became increasingly an arena for bribery, tactics and anarchy. The right of veto was based on the principle of the equality of all nobles in the assembly and meant that all decisions were to be taken unanimously and thus a personal veto of a proposal was sufficient to make the same decision. As a result, political life was paralyzed, all reform work stopped and foreign powers and magnates through contacts with individual nobles could prevent the adoption of unwelcome proposals for them.

Finally, to the internal turmoil also contributed the Catholic counter-Reformation, which from the end of the 16th century drastically reduced the religious tolerance in Poland, including several massacres on Jews as a result. Laws were enforced as limited non-Catholic rights. In Orthodox eastern Poland, the Catholic recovery culminated with the union in Brest-Litovsk in 1596. Then the Unitarian Church, whose followers recognized the Pope as the head of the Christian Church, was created on condition that they be allowed to maintain the Orthodox doctrine.

Poland from the divisions to the First World War (1772-1914)

During the 18th century, Russian, Prussian and Austrian involvement in Poland’s internal affairs increased. resulted in the Polish war of succession. The internal divide was actively maintained, especially by Catherine II of Russia, who wanted to maintain Poland as a weak buffer zone against competing European great powers. A Turkish-backed Polish uprising against the Russian repression of 1768-72, the Bar Confederation, gave Russia, Prussia and Austria a pretext to intervene in 1772 according to a Prussian division plan. Prussia during Frederick II took West Prussia with its economically important trading cities, Austria under Maria Teresia of Lesser Russian Galicia and Lodomeria, while Catherine seized Belarusian territories adjacent to the Russian border.

Following a new Polish uprising under General Tadeusz Kościuszko, the division of Poland was completed in 1793 and 1795. Russia took all territories east of the Nemunas and Bug rivers, including Lithuania, Austria took the whole of the Lesser Poland and Prussia took the Greater Poland, Masovia and Danzig. Poland ceased to exist as an independent state, and the Poles became subjects of multinational empires, governed by autocratic principles.

The institutions of the noble republic disappeared, while its cultural foundations were preserved, not only in eastern and central Europe but also in France, to which Polish patriots moved, inspired by the ideal of freedom of the French Revolution. Partly as a reward for the struggle of the Polish exile legions on the French side in the Revolutionary War, Napoleon established in 1807 parts of the Polish Prussian duchy of Warsaw under French supremacy. However, this came under Russian rule after Napoleon’s failed war against Russia in 1812, and the Vienna Congress in 1814-15 confirmed the division of Poland.

The majority of the duchy was transformed into the so-called Congress-Poland after the Napoleonic Wars, and the area was given its own constitution, seam and army, but as little as the Grand Duchy of Poznań (1815-48) and the Republic of Kraków (1815-46) was an independent political entity. The Russian tsar was king of Congress-Poland and, after some initial liberal years, vigorously exercised his autocratic rule, which drove two major Polish uprising movements.

The first was the November Uprising of 1830, inspired by the French July Revolution and Tsar Nicholas I’s despotic regime. The uprising, which grew into a general Polish-Russian war in 1831, failed due to internal fragmentation and lack of support from the oppressed peasants. Internal self-government was reduced in the so-called organic statute of 1832, and many Poles who avoided Siberian deportation or forced enrollment in the Russian army chose to emigrate.

The second uprising took place in January 1863 and was based in part on the reform hopes that Tsar Alexander II’s rule aroused, partly a flourishing Polish nationalism with roots in the ideas of romance. One of the leading figures behind the idea of the country’s restoration was Lithuanian-born poet Adam Mickiewicz. In the absence of a Polish army, the revolt was entirely based on hopes of French support, which, however, failed. After the uprising after more than a year, the Congress-Poland was incorporated in Russia, and a hard-fought policy of reform took place. However, the reform hopes were not completely met, as Alexander abolished the peasants’ livelihood in 1864, with the result that Russian rule gained popularity among poor Polish peasants. After the January uprising, many Poles in Russia abandoned the method of rebellion and invested in reform efforts for increased Polish self-government, while revolutionary ideas had greater vitality among Poles in Austria and in exile.

In the second half of the 19th century, modernization began in the Polish parts of the empires. Warsaw and Łódź developed into industrial cities, an industrial bourgeoisie emerged and a working class was formed. Many Poles moved to industrial centers in Germany. Both bourgeois national-democratic and socialist Polish parties emerged during the last decades of 19th century in Polish Russia. During the 1905 wave of revolution, the latter were divided; while a smaller group, led among others. by Rosa Luxemburg, who supported the Russian social democracy, another larger group developed in the reformist and nationalist direction. A leading figure in this was Józef Piłsudski.

In Austria, where universal suffrage for men was introduced in 1907, a Polish farmer’s party was formed, while the Polish minority in Prussia (Germany) was oppressed both culturally and politically, with increasing contradictions between Germans and Poles as a result. Ethnically constructed parties showed the existence of a Polish identity, but there was hardly any uniform political goal for them.

World War I, the rebirth and the interwar period (1914–39)

At the outbreak of the First World War in 1914, the Poles were divided. The belligerent states outbid each other to receive Polish military assistance. Anti-Russian Polish legions led by Piłsudski actively fought on the part of the central powers and, after German troops conquered all of Poland, formally took over power in a newly established so-called Polish kingdom in 1916. In fact, the area was ruled by German military.

Other Polish groups pinned hopes on Russian autonomy promises and struggles on the part of the Tsar army, and a third exile group relied on the Western powers and formed a Polish National Committee in Paris. It can hardly be argued that any of these groups were directly behind the creation of the so-called Second Polish Republic on the day of wartime, November 11, 1918. Poland’s rebirth was included in the fourteen points launched by US President Wilson as the basis for a general peace, and Piłsudski, who, after contradictions with the Germans interned in Germany, could, upon return, take possession of this state. Its real boundaries were then established partly in the Paris Peace 1919-20, partly through referendums ordered by the victorious powers, and also by territorial conquests from surrounding newly formed states.

The most extensive war was fought against Bolshevik Russia 1919-20 and ended with a border draw straight through Belarus, Ukraine and Lithuania (see the Polish-Russian war). Vilnius was occupied by the Poles in 1922, which led to tense relations between Poland and Lithuania throughout the interwar period (see Polish-Lithuanian War). See also the Polish-Ukrainian War.

The new Polish society was heterogeneous. One third of the residents were ethnic minorities. The ethnic and social strata often went hand in hand; Germans and Jews dominated among the bourgeois urban population, while Ukrainians and Belarusians in the east were poor peasants. Anti-Semitism was widespread.

Reconstruction after the First World War was made more difficult by the undeveloped agricultural economy and by the overpopulation. Land reform and industrialization received insufficient support. In light of this dark social image and the lack of experience of state and community building, the political divide in postwar Poland appears almost natural. Weak minority and coalition governments were common during the first interwar years, and political life was polarized.

After Poland was given a constitution in 1921, Piłsudski resigned as head of state, but in a bloodless coup in 1926 he regained power and led the country as a dictator during the years of economic depression. The dictatorship can be described as authoritarian, supported by the army, a conservative aristocracy and a charismatic leadership, with a non-communist but otherwise unclear political program.

After Piłsudski’s death, the power was taken over by a military junta. One of its members was Foreign Minister Józef Beck, who in the 1930s tried to balance the Polish foreign policy between Nazi Germany and Stalinist Soviet Union, both of which showed dissatisfaction with their respective borders with Poland. German dissatisfaction was reinforced by Nazi-influenced German groups in Poland. Beck sought to maintain the 1921 alliance with France, which, however, along with Britain, ran an appeasement policy against Poland’s aggressive neighbors. At the same time, Poland itself showed aggressive foreign policy intentions by taking in 1938, with the great powers of the great powers, the rich Teschen area from Czechoslovakia.

Poland during World War II (1939–45)

The German army’s attack on the militarily weak Poland. September 1, 1939 meant that the Second World War broke out. The attack was preceded by a non-attack agreement between the Soviet Union and Germany, the so-called Molotov-Ribbentrop pact, which also included an agreement on a division of Poland. In accordance with the agreement, the Soviet Union also attacked Poland on 17 September. Large areas were incorporated directly into the invading states, both of which committed unbelievable atrocities against the population.

Two million Polish Jews were taken by the Germans to barred areas, while the Soviet power deported hundreds of thousands of Poles to Siberia. In Katyn near Smolensk, the Soviet security service NKVD murdered over 4,000 Polish officers in 1940. A Polish government and army were constituted in Paris, but soon moved to London.

Following Hitler’s attack on the Soviet Union in June 1941, the whole of Poland was ruled by the Germans, while the exile government was approaching the Soviet Union. According to a Nazi general plan, a campaign for cultural Germanization of Poland, which had the status of German general government, was initiated, and Polish population groups began to move either east or to slave labor in Germany to make room for German migrants. The planning also included a number of extermination camps in the General Government, which greatly contributed to the deaths of approximately 6 million European Jews. In 1943, the Jews of the Warsaw ghetto revolted. This was knocked down, and the ghetto leveled with the ground by the Germans.

At the 1943 Peace Conference in Tehran, the Western powers had accepted that Poland would fall within the Soviet sphere of interest, and in January 1944, the Soviet liberation of Poland began. By reliable communists, Stalin, who after the revelations about Katyn in 1943, broke with the Polish government, organized a new Polish army and set up a national liberation committee, the so-called Lublin government. In competition with the exile government in London, it declared itself in connection with the Soviet advance to Poland’s only legal government, and non-communist resistance groups were arrested. This is the background to the tragic Warsaw uprising in 1944.

Prior to the Soviet army’s expected conquest of Warsaw, a large part of the residents stood up to the non-communist resistance movement’s call against the Germans. To show the Poles’ dependence on Soviet support and to remove parts of the non-communist resistance, Stalin held back the Soviet offensive, with the result that the Germans crushed the uprising during the great blood spill. In June 1945, with the approval of the Western powers, a unifying government was established with a large communist dominance. Communist Bolesław Bierut was appointed President of the Cabinet (President). Poland lost large tracts of land to the east (compare the Curzon Line), but was compensated in the west by German territories up to the Oder – Neisse line, from which millions of Germans had moved or forced to move.

Postwar

After the war, a Sovietization started with Bierut as the driving force. The pattern is recognizable from the rest of Eastern Europe: guided elections led “the United Workers Party” to power, Soviet ideology, Soviet culture and a Soviet-like constitution were enforced, security services were expanded, foreign and trade policy was coordinated with Soviet, industrial planning regulated economic life and regulated economic life. dramatically the entire infrastructure of society. Many Poles fled to the West.

A unique feature of the Polish development was that the collectivization of agriculture was carried out only to a small extent. Another was the important role of the Catholic Church as the bearer of the Polish cultural heritage and thus as an active community force; In 1953 Cardinal Stefan Wyszyński was interned after opposing worldly involvement in church affairs. In connection with the stalinisation, in 1956 violent labor unrest arose in Poznań, which was abolished with violence.

The regimes Władysław Gomułka, 1956-70, and Edward Gierek, 1970-80, both made valiant efforts to gain popular support and legitimacy by renouncing Poland’s national culture and, in Gomułka’s case, by interrupting agricultural collectivization. Both were forced into a difficult balance in order not to simultaneously damage the communist regime. In both cases, expectations of economic and political liberalization soon changed into a strong and widespread dissatisfaction with the negative economic development. The similar result of Gomułka’s uncompromisingly tough economic line and Gierek’s extravagant investment in foreign loans and consumer goods became higher food prices, which led to strikes, demonstrations and riots, which in turn met with repression.

A further two events in the second half of the 1970s contributed to weakening Gierek’s and communism’s legitimacy. One was that in October 1978, Polish Cardinal Karol Wojtyła, Archbishop of Kraków, was elected Pope under the name of John Paul II. The event triggered a combined religious and nationalist euphoria in the home country, which was further reinforced when the Pope made visits to Poland the following year. The second was that the workers with their material demands and the intellectuals with their nationalistic, cultural aspirations were approaching each other and preparing for a unified political action against the Polish communist regime. Opposition intellectuals formed a committee of workers’ defense (KOR) in 1976.

In August 1980, a strike broke out at the Lenin Yard in Gdańsk. Led by electrician Lech Wałęsa, it spread quickly and forced the government into negotiations. In September, the independent trade union Solidarity (Polish Solidarność) was formed to lead the workers’ case, with Wałęsa as chairman. Most occupational categories and social classes joined up with the demands for economic and social reforms driven by the ever stronger Solidarity, including members of the Communist Party. A bond was formed between church and trade union.

In order to put an end to the turmoil in Polish social life and to satisfy Soviet demands for order, the newly-appointed party and government general, Wojciech Jaruzelski, introduced a state of emergency on December 13, 1981, which was not terminated until 1983. Real negotiations between the government and Solidarity began in 1988 and the following year. reaped the latter great successes in partially free elections to the Sejm.

Poland after the fall of communism

In 1989, Poland’s first non-communist government was formed since the war, with the solidarity member Tadeusz Mazowiecki as prime minister. In January 1990, the Communist Party dissolved, and in December Lech Wałęsa was elected president of an economically pressured and politically divided Poland. The first completely free parliamentary elections took place in 1991. The 1993 elections brought the former Communist Party, now under the name Democratic Left Alliance (SLD), to power.

The Leftist also stood in 1995. Socialist Aleksander Kwaśniewski defeated Wałęsa in the presidential election. In 1997, a non-socialist coalition took power under the leadership of Jerzy Buzek (born 1940). The new government again included old Solidarity activists. After four years, the pendulum swung back when the left won the elections in 2001. It swung again in 2005 when national conservative Lech Kaczyński won the presidential power. Two weeks after the presidential election, his twin brother Jarosław Kaczyński’s party, the conservative but economically neo-liberal PiS, became the largest party in the parliamentary elections.

The following extra election in 2007 disappeared PiS’s two coalition partners, the ultra-conservative Polish family delayed union (LPR) and the populist Somoobrona (Self-defense), while PiS’s competitor, Civic Platform (PO) during kasjuben (kasjuberna is a small Slavic minority around Gdansk) Donald Tusk became almost twice as large as PiS. Tusk was appointed new prime minister and was able to form a coalition government consisting of ministers from the PO and the Polish People’s Party (PSL).

The PO government was renewed in the autumn 2011 elections, which was the first time in Poland’s democratic history a sitting government was re-elected. Tusk’s party mate Bronisław Komorowski defeated Jarosław Kaczyński in an early presidential election in June/July 2010, following the tragic death of Lech Kaczyński in a plane crash. In the 2015 presidential election, PiS candidate Andrzej Duda unexpectedly defeated incumbent President Komorowski. When PiS also triumphed in the 2015 election, the party had great opportunities to implement its policy.

Local self-government in Poland has been strengthened compared to the communist era, which has accentuated historically contingent regional differences in political preferences and economic development. The metropolitan region and the western regions are developing faster, while peasant conservatism lives stronger in the economically less developed former Russian areas in the east and south. Poland’s pervasive political and economic transformation and good relations with neighboring countries have attracted international respect, as confirmed by its accession to NATO in 1999 and the EU in 2004.

Throughout the period since 1989, but especially since Poland’s accession to the EU in May 2004 (including the European crisis year 2009), Poland has experienced strong economic growth.

Poland supported the US-led interventions in Iraq and Afghanistan, which, however, were challenged at home. An unresolved controversy was whether Poland in 2003 lent an airport with associated buildings to the US military for capture and storage. Poland did not participate in Libya’s international efforts in 2011.

2015-19 was marked by Poland’s prolonged and sharp conflict with the EU regarding Jarosław Kaczyński and the PiS government’s reform of the judiciary, which was considered to violate the EU rule of law criterion. The consequences of Poland’s laws were criticized by the EU for threatening the independence of its courts in relation to political power. Poland’s media policy has also been criticized by the EU for contravening the Union’s democracy criterion, which requires free media in general and public service in particular. According to the EU, not having free media becomes a threat to a functioning democracy because a functioning democracy requires well-informed citizens.

However, there is no Polish endeavor to leave the EU, but criticism of what is considered by PiS to be the Union’s supremacy, which runs counter to the Member State’s own political ambitions.

The PiS government has wanted to strengthen ties with the United States and pledged $ 2 billion to the country to cover the costs of a permanent US military presence in Poland.

Secretary-General of the Polish Communist Party

| 1943-48 | Władysław Gomułka |

| 1948-56 | Bolesław Bierut |

| 1956 | Edward Ochab |

| 1956-70 | Władysław Gomułka |

| 1970-80 | Edward Gierek |

| 1980-81 | Stanisław Kania |

| 1981-89 | Wojciech Jaruzelski |

Historical overview

| about 350,000 BC | Neanderthal people in southern Poland. |

| about 40,000-10,000 BC | Central Poland is populated; from about 14,000 BC the northern parts are also beginning to be populated. Contacts with Southern Scandinavia. |

| about 4,500 BC | Agriculture is introduced in the south. |

| about 2,000–700 BC | The Bronze Age. Long distance trade contacts. Amber Exports. |

| about 700 BC – 400 AD | The Iron Age. From about 120 BC trade with the Roman Empire. |

| about 400–900 AD | Poland is populated by Celtic, Germanic, Baltic and Slavic groups. Technical advances in agriculture and industry contribute to the emergence of state-like societies. At the end of the period, the West Slavic Poles begin to dominate the coastal area. |

| 960s | Mieszko I of the Piast Dynasty organizes the kingdom; Roman Christianity is assumed. |

| 1000 | Archdiocese of Gniezno approaches Poland to the west. |

| 1025 | Boleslav I becomes Poland’s first king. |

| 1320-70 | Strong territorial expansion. |

| 1385 | Personnel union between Poland and Lithuania. |

| 1410 | German words are defeated at Tannenberg. |

| 1493 | The noble sejm meets for the first time. |

| 1500s | Economic and cultural golden age. |

| 1569-1795 | The noble Republic, Rzeczpospolita, is introduced; realunion is formed between Poland and Lithuania. Internal fragmentation and military hardships. |

| 1572 | Election kingdoms are introduced. |

| 1648-54 | Parts of Ukraine are lost to Russia. |

| 1660 | The peace in Oliwa forces Poland to write off claims on the Swedish krona. |

| 1700s | The influence of Russia, Prussia and Austria in Poland’s internal affairs is increasing. |

| 1733-38 | Polish Succession War. |

| 1772 | Poland’s first division. |

| 1793 | Poland’s second division. |

| 1795 | Poland’s third division causes the state of Poland to disappear. |

| 1807-15 | Duchy of Warsaw. |

| 1815-64 | Congress-Poland in personnel union with Russia. |

| 1830-31 | The November uprising leads into Polish-Russian war. |

| 1863-64 | Congress-Poland is incorporated in Russia. |

| 1918 | Poland resurfaces at the end of the First World War. |

| 1919-20 | Polish-Russian war on Poland’s eastern border. |

| 1922 | Lithuanian Vilnius is occupied by Poland. |

| 1926 | The coup d’état gives Piłsudski dictatorial power. |

| 1939 | German attack on Poland September 1 begins World War II; September 17, the Soviet Union also attacks Poland. |

| 1943 | The uprising in the Warsaw ghetto. |

| 1944 | The Soviet liberation of Poland begins and the Lublin government is established. Warsaw Uprising. |

| 1945-89 | Soviet period. |

| 1980 | Strike at Lenin Yard in Gdańsk; Solidarity is formed. |

| 1981-83 | An emergency permit prevails. |

| 1989 | A non-communist government is formed. |

| 1991 | Free parliamentary elections take place. |

| 1999 | Joining NATO. |

| 2004 | Become a member of the EU. |

| 2010 | President Lech Kaczyński is killed in an air crash in the Russian Federation along with several other Polish dignitaries. |